The following appeared in The Spinoff, written by guest writer Helen Glenny, with accompanying illustrations by Ezra Whittaker.

As we approach the two-year anniversary of the first COVID test taken in Aotearoa, there’s now a variety of test types and different ways of taking samples. What’s the difference, and when should you use them?

Our COVID-testing options are about to broaden: as of tomorrow, we’ll be able to take rapid antigen tests under the guidance of a pharmacist. Much like you see on a pregnancy test, one line shows that the test worked, and two lines indicate a positive result. At the same time, community testing centres and your local GP will continue to use the PCR tests we’ve become familiar with.

So when should we use rapid tests, and when should we go to a testing centre? Clinical microbiologists Matthew Blakiston of Labtests and Juliet Elvy of Medlab South (laboratories of the Awanui network) break down how these tests work, and what role each will play in managing COVID over the summer holidays.

PCR tests

What are PCR tests for?

PCR tests are the gold standard for diagnosing cases of COVID-19. “It’s what we’ve been using since the start of the pandemic. It’s tried and tested, and it’s sensitive and reliable,” says clinical microbiologist Dr Juliet Elvy. If you have flu-like symptoms, or are a close or casual contact of someone with COVID-19, you’ll need a PCR test.

However, PCR tests take teams of skilled lab scientists and technicians to process, and for that reason, they take time. For frequent surveillance testing, when the risk of catching COVID-19 is relatively low, other test types can lend a hand, allowing New Zealand labs to focus on diagnosing positive cases faster.

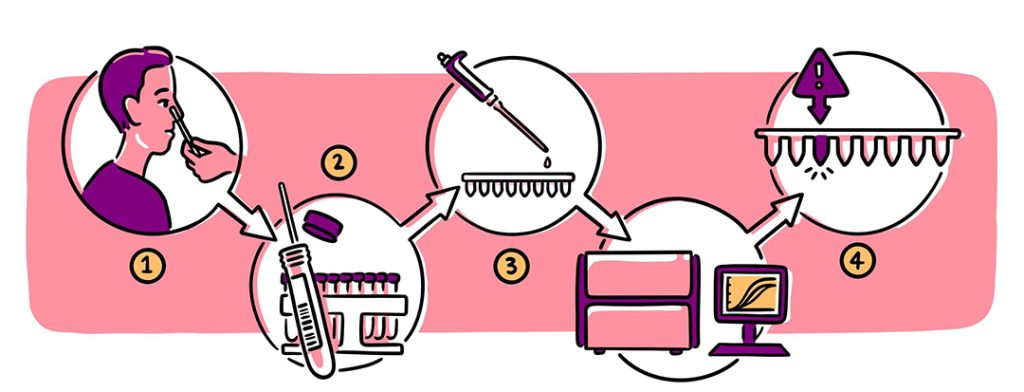

How do PCR tests work?

PCR tests are a type of nucleic acid amplification test, or NAAT. “They detect minuscule amounts of RNA from the virus,” says Dr Matthew Blakiston. Samples that come in from community testing centres and GPs get logged and loaded into an PCR analyser. During the PCR process, enzymes and other reagents specific to the virus, are used to amplify small amounts of COVID-19 RNA, if there’s any present in the sample. “This process uses cyclical repeated reactions to copy any viral RNA present. Each cycle effectively doubles the amount of nucleic acid present until it reaches a level where it’s detectable by specific probes that bind to COVID-19 nucleic acid (RNA). Once there is enough RNA, with enough bound probes, it shows up as a fluorescent signal,” says Blakiston. If a sample doesn’t have any COVID-19 in it, there’s no RNA to be amplified, the probes have nothing to bind to, and the test comes back negative.

Specimens that are positive by PCR testing are associated with a CT value (a cycle threshold). A CT value is how many amplification cycles are needed to make the RNA detectable. “Generally, most tests taken early in acute infections take between 15 to 25 cycles to become detectable,” Blakiston says. Sometimes PCR results are referred to as “weak positives”; “There is no universal definition, but this generally refers to positive tests that are only detectable after about 35 cycles.”

How long does it take to get a result?

Generally, you’ll be waiting between 24 and 72 hours for a PCR result.

Your test has to travel to a laboratory with a large PCR analyser. Even though more of these machines are being distributed to our regions, most of them are still in our main centres. Preparing the sample for testing is a hands-on process that takes one to two hours. The tests take four to six hours in the machine, and on top of that there’s the time needed for staff to log the test, to make sure it’s identifiable.

Where is the sample taken from?

Currently, there are three ways a PCR sample can be collected: using a nasopharyngeal swab (high up the nose), by swabbing the throat and nose (only a few centimetres up the nose), and through saliva. The site doesn’t radically change how the test works or how long it takes. “By and large it’s the same technology, the same machines, with a few tweaks in the pre-PCR preparation stage,” says Blakiston.

Nasopharyngeal swabs and a combined throat and nose swab perform equally well. Saliva testing is also comparable in the early phase of acute COVID-19 infection. Saliva tests can be a bit harder for labs to work with; sometimes there can be contamination with food, not enough saliva provided, or the sample can be a bit gloopy. “There is a place for saliva, though, because it’s more comfortable to collect,” says Elvy. “A saliva test also doesn’t require any supervision.”

How reliable are PCR tests?

Nasopharyngeal PCR testing, when performed early on an acute symptomatic patient, will pick up positive Covid cases around 95% of the time. However, when testing is carried out later in the course of the infection, the chance of a PCR test failing to detect COVID increases. The false positive rate for PCR testing is very low (likely < 0.1% in the setting of quality-controlled and appropriately supervised testing).

Rapid antigen tests

What are rapid antigen tests for?

Rapid antigen tests (RATs), soon to be rolled out in New Zealand pharmacies, are a fast, accessible way of screening for COVID-19. These could be people working at low-risk borders, in air travel or in healthcare settings, or people who are seeing vulnerable friends or family members often, and want to identify any infection before they become symptomatic. They’e also being accepted by some countries as acceptable pre-departure tests.

How do rapid antigen tests work?

Rapid antigen tests detect the spike protein (“antigen”) of the Covid virus as opposed to the RNA in a PCR test. “They’re pretty easy to do,” says Blakiston. “You take the swab yourself, put the swab in a tube of buffer and mix it around, and then squeeze a few drops of the buffer onto a window in the test cartridge. The fluid then sucks down across a membrane. You wait 10-15 minutes to read the result “You get one line to show the test has worked (marked ‘C’ for control) and a second line (marked ‘T’ for test) if the test is positive.”

Where is the sample taken from?

RATs are typically nasal or throat and nose tests, but you don’t have to put the swab very far up your nose, making it more comfortable than nasopharyngeal PCR tests. The UK has been using RATs for a while; they refer to them as lateral flow tests. “One misconception is around saliva antigen tests,” says Elvy. “Rapid antigen tests are only nasal or throat swabs at the moment, there isn’t a good saliva antigen test out there anywhere in the world.”

How reliable are RATs?

They’re less reliable than PCR tests with an overall sensitivity of 75-80% compared to PCR testing. “If someone has a low CT value (representing a high viral load), under 25-ish, the test will pick up the majority of these cases, but not all of them. In theory, they pick up most people who are infectious at the time of testing, who have a high viral load,” Blakiston says.

If you have COVID-19, your viral load changes over the course of the illness, sometimes rapidly. You can have a low viral load right at the start of the infection, so you might test negative on an RAT, and a low viral load later in the infection, when you might also test negative. Because of the greater risk of false negative results they are not ideal for testing those with a higher probability of COVID-19 such as contacts or people with symptoms. RATs are best used in scenarios where people are testing frequently, around two to three times per week. With frequent testing, even if the test doesn’t pick up an infection early on, it’ll likely pick it up a few days later, when you have a higher viral load.

There is a risk of false positives with RATs, and with low levels of COVID in the community, these false positives could outnumber actual true positive COVID cases. “In low prevalence areas, which is most areas at the moment outside of certain pockets of Auckland, then if you did get a positive rapid antigen result, it would actually be more likely that it’s a false positive than a real result,” says Elvy. This is one reason why all positive RATs will need to be followed up by PCR tests.

Given this lower reliability, why use RATs?

If you’re in a setting where you need to be tested frequently, the use of RATs shifts the burden away from PCR testing, which takes a lot of manpower. If you become infected, you are likely to pick up an infection eventually if you’re being tested regularly with RATs.

Who should get a rapid antigen test?

If you don’t have COVID symptoms and haven’t been in contact with anyone with COVID-19, then RATs are a good option. Elvy sees a place for RATs in our overall COVID strategy: “A negative test will be part of the measures we take to keep our loved ones safe, which includes vaccinations, staying home when sick, staying home if you’re a contact of a case, mask use, washing hands and cough etiquette. It’s one additional part of the safety mechanisms that are already ingrained in our everyday behaviours.”

Other COVID-19 tests

A few other COVID tests are being used in other settings. Most of our hospitals are using rapid PCR tests, which can give results in as little as 30 minutes. This can be useful to find out quickly if patients need to be isolated from others. “Most of those rapid PCR platforms are as good as the slower ones, but we simply don’t have enough of them available. They’re under massive global constraints, the whole world wants them, so they’re being rationed,” says Elvy.

You might also hear about antibody tests. These are blood tests that detect your immune response to viral infection or vaccination. “We used these when we were interested in investigating historical infections during our elimination phase, when we would often get these very weak positive PCRs. The antibody could help us figure out whether that was because they’d had a past infection,” says Elvy. For most of the general public antibody testing has no role to play.

The bottom line

If you have COVID symptoms, or are classified as a contact of someone with COVID-19, follow Ministry of Health guidelines, and get a PCR test. If you’re asymptomatic and simply want to be careful, take a rapid antigen test as close as possible to the event where you could potentially spread the virus. But remember, rapid antigen tests are just one of many protective measures you can take: get vaccinated if you can, wear a mask, wash your hands, cough into your elbow, and if you have any symptoms, get a PCR test and stay at home.

This content was created in paid partnership with Awanui.