A new collaboration between clinicians, laboratory teams, and researchers is working to reduce potentially very serious side effects for patients prescribed capecitabine or 5-fluorouracil (5FU) as treatments for cancer.

“Severe side effects from 5FU and capecitabine can be debilitating, and we want to find any way we can to help prevent this from occurring,” says Dunedin Oncologist Professor Chris Jackson. “This is why we approached Awanui and the University to see if we could get this testing available in our backyard.”

5FU and capecitabine are metabolised (processed in the body) by an enzyme called dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD for short and the gene which codes for this is called DPYD). Some people have reduced amounts of this enzyme meaning the cancer drugs build up in their body causing unexpected and severe side effects. These include patients being admitted to hospital, needing intravenous fluids, intravenous feeding (total parenteral nutrition) and on rare occasions patients have died from this complication.

While some labs overseas have been able to test for this, it was unavailable in New Zealand so setting up DPYD genotyping was a “no-brainer” says Jenny Grant, Head of Molecular Pathology at Awanui Labs in Dunedin.

“Cancer patients are already going through enough without the drug they are given to help them potentially leading to severe to life-threatening toxicity. If we can identify patients who have variants in the DPYD gene, and their oncologist can adjust their 5FU dose to reduce the risk of any potential severe to life-threatening toxicity, then this outcome is hugely rewarding.

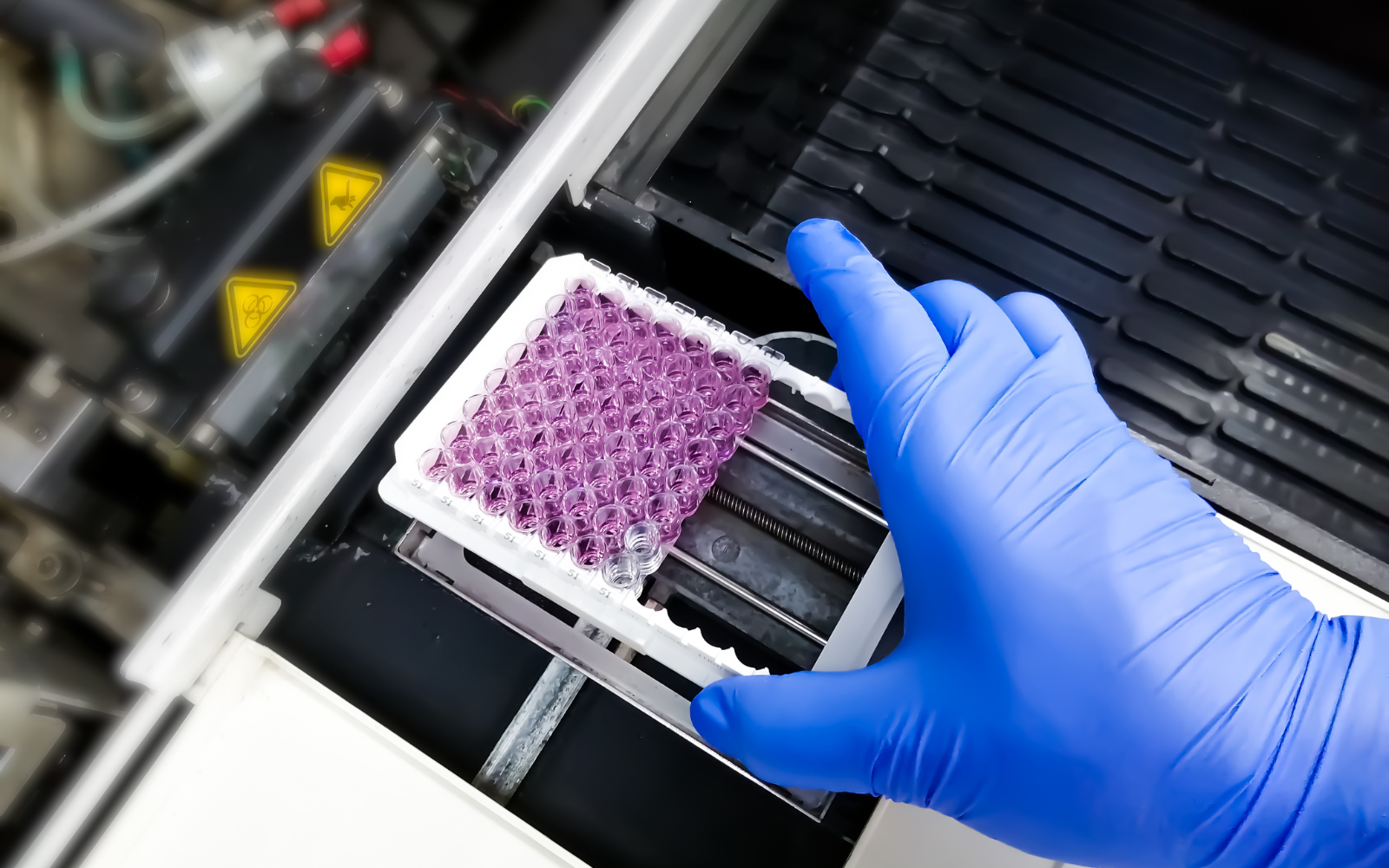

In collaboration with the Medical Laboratory Science Programme at the University of Otago, Awanui Labs have developed and validated a DPYD genotyping assay for routine use at the Dunedin lab.

“This collaboration brought together people with different skill sets, enabled access to equipment required to validate the test, and made setting up DPYD genotyping a reality. Between January 2023 and February 2024 both technical and clinical validation was carried out, with routine testing being offered since May 2024,” says Jenny.

“We initially expected this to be a low volume test with around 100 tests a year from the Otago-Southland region. However, since May this year, the team have carried out over 160 DPYD genotyping tests for patients across Otago, Southland, Nelson, Marlborough, and South Canterbury”.

“Although the number of patients at risk from DPD deficiency is low, the genotyping gives them and their oncologist a better understanding of the level of risk from 5FU and capecitabine. We strive to get a result within one week from the sample arriving in our Dunedin laboratory. With the help of electronic ordering, and all going well, the oncologist will have the DPYD genotyping result when the patient attends their oncologist appointment to inform discussions around their treatment.

“This testing is about improving health and saving lives. It gives more information to the oncologist, so they are better informed about any potential toxicity risks and can make better decisions about treatment options and next steps for their patients,” says Jenny.

“This collaboration is definitely ahead of the curve, and while others are now looking to catch up, Awanui is still offering this test faster than any other lab in New Zealand, and it’s making a huge difference in the clinic already,” says Professor Jackson.

“Now, we can have the results available before we even meet patients in clinic, making it easier to predict who might get side effects, and plan treatment options accordingly. The “can do” attitude of the team has been outstanding and shows a deep commitment to providing the best care for the people of the south.”

Associate Professor Tania Slatter, Director of the Medical Laboratory Science Programme at the University of Otago says this project demonstrated how good collaborations can benefit patients and contribute to delivering better health outcomes.